Spina Bifida

Spina bifida is a rare neural tube (the structure in a developing embryo that encompasses what eventually becomes the baby's brain and spinal cord as well as the tissues that enclose them) birth defect in which the lower portion of the neural tube fails to close properly, causing the spinal cord to be unable to close or develop properly while in the womb. Spina bifida occurs in approximately 1 out of every 1,000 live births in the United States and can be identified on a fetal ultrasound as early as the second trimester.

About Spina Bifida

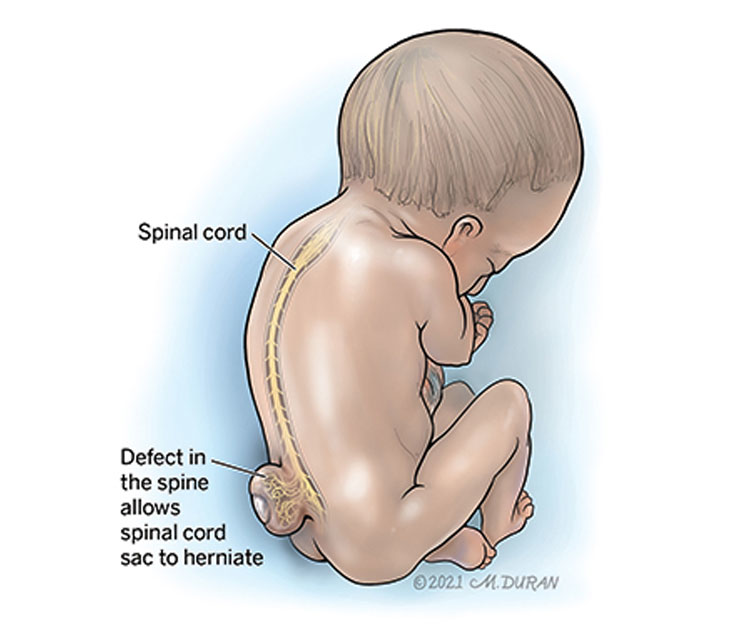

The spinal cord develops from the neural tube, which typically forms and closes between the 17th and 30th day after conception. In babies with spina bifida, the lower portion of the neural tube does not close properly. As a result, the spinal cord and backbone (the series of vertebrae that make up the spine and protect the spinal cord) also fail to close and develop properly, causing the child to be born with an opening in their lower spine. This can result in a protrusion of a fluid-filled sac containing the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue. Exposure of this fluid-filled sac to the amniotic fluid that surrounds the growing fetus can cause damage to the spinal cord and nerve tissue.

Spina bifida can be classified as “open” or “closed.” Open spina bifida has no skin covering the defect, which exposes the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue to the amniotic fluid that surrounds the growing fetus. Closed spina bifida has skin covering the lesions (openings in the spinal cord) and is typically associated with better outcomes. The different types of spina bifida are classified according to their appearance.

Types of spina bifida include:

- Myelomeningocele, an open form of spina bifida and the most severe type, is categorized by a balloon-like structure or sac filled with fluid that contains the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue and protrudes from the baby’s back.

- Myeloschisis, an open form of spina bifida, is categorized by the lesion (opening in the spinal cord) on the baby’s back appearing flat with no covering membrane (no layer of skin covering the opening).

- Meningocele, a closed form of spina bifida, is categorized by the fluid-filled sac protruding through the baby’s back but the sac only contains spinal fluid and does not contain nerve tissue.

- Lipomyelomeningocele, a closed form of spina bifida, is categorized by a fatty tissue mass (under the skin) that attaches to the lower portion of the spinal cord.

Spina bifida can also be classified according to its height level (with level 1 being closest to the neck) and where it occurs along the spine. The spine’s vertebrae can be divided into regions: cervical (neck), thoracic (mid back) lumbar (lower back), and sacral (very low back). A lumbar level 4 defect, known as an L4 lesion, is the most common site for spina bifida.

Symptoms of Spina Bifida

In the more common “closed” forms of spina bifida, there typically aren’t any symptoms because the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue aren’t exposed. Once your baby is born, you may be able to detect signs, such as an abnormal tuff of hair, small dimple, or birthmark, on your newborn's skin in the area where the skin covers the lesion.

In the more severe “open” forms of spina bifida, the spinal canal remains open along several vertebrae and the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue are exposed.

Symptoms of spina bifida may include:

- A buildup of cerebrospinal fluid, leading to hydrocephalus (increased pressure in the brain due to the increased fluid)

- Weakness or paralysis of the legs

- Urinary incontinence

- Bowel incontinence

- Lack of sensation in the skin in the lower body

Causes of Spina Bifida

While the exact cause remains unknown, spina bifida is thought to be a result of a combination of genetic, nutritional, and environmental risk factors, such as a family history of neural tube defects and folate (vitamin B-9) deficiency. Whites and Hispanics are at a higher risk for developing spina bifida. Female fetuses are more likely to be diagnosed with spina bifida than male fetuses.

Risk factors for spina bifida include:

- Diabetes

- Folate deficiency

- Family history of neural tube defects

- Increased body temperature

- Obesity

- Some medications, such as anti-seizure medications

Complications Associated With Spina Bifida

Spina bifida is not associated with any health risks for the pregnant mother. Spina bifida is usually associated with problems in the baby’s brain. The most common of these is the Chiari II malformation, in which the cerebellum (area at the back and bottom of the brain behind the brainstem) is pulled to the rear of the fetal skull and bulges down into the cervical spine canal, blocking the normal flow of the fluid that protects the brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid or CSF). This often results in ventriculomegaly, which is an enlargement of the fluid-filled compartments of the brain. Ventriculomegaly can be diagnosed in the fetal brain and is often associated with hydrocephalus (increased pressure in the brain due to the increased fluid), which is only diagnosed after the baby is born. Ventriculomegaly and decreased leg movement may be noted on an ultrasound as the pregnancy progresses.

Spina bifida can also be associated with an abnormal curvature of the spine (scoliosis) as well as abnormal positioning of the feet and ankles (clubfoot or valgus deformity). Spina bifida is rarely associated with chromosomal abnormalities.

The long-term outcome for babies diagnosed with spina bifida is dependent on several factors, including the severity of the spina bifida and the need for a cerebrospinal fluid shunt. Problems with the ability to walk are common, with some children potentially needing assisted walking devices while others may require the use of a wheelchair. Children with spina bifida typically experience learning differences and some may have lower IQ’s than their siblings, but normal intelligence is possible. Spontaneous voiding (urinating) is rare and to develop urinary control, an intermittent catheterization of the bladder (placing a tube into the bladder) may be necessary. Sexual dysfunction is not uncommon; however, women with spina bifida can carry out successful pregnancies. The development of kidney failure seems to be a determining factor for long-term survival.

Diagnosing Spina Bifida

A pregnant mother typically has a screening during the second trimester that involves a blood test known as an alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) test. If the test reveals high levels of alpha-fetoprotein, the mother’s developing baby could have a neural tube defect, such as spina bifida, and an ultrasound is scheduled to confirm the diagnosis. Most cases of spina bifida are diagnosed at the time of a routine anatomy ultrasound at around 20 weeks (5 months) of gestation.

At the time of the ultrasound, a fetus with spina bifida will appear to have a “lemon-shaped” head. These indentations of the skull will go away as the pregnancy progresses. Additionally, the structure in the back of the brain (the cerebellum) will be pulled backward in a “banana sign," which indicates a Chiari II malformation (a defect of the spine in which some portion of the brain stem and its surrounding tissue descends into the cervical spine). More careful ultrasound of the lower part of the spine will often detect a protruding sac if a myelomeningocele is present. 3D ultrasound can be used to locate the level of the spina bifida. Ultrasound can also be used to evaluate for the presence of normal leg movement and whether the developing fetus has clubfoot or valgus deformity (an abnormal positioning of the feet and ankles).

Pregnancy With Spina Bifida

After the initial ultrasound evaluation, you will likely be scheduled for fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A fetal MRI is similar to a CT scan but does not involve X-rays or radiation. Instead, a special magnet is used to produce images of the structures in the fetus that cannot be observed easily with ultrasound. A fetal MRI is safe for both you and your baby. You will likely need ultrasounds every 3 to 4 weeks to monitor the amount of fluid in the ventricles in your baby’s head. You may also meet with a genetic counselor and a pediatric neurosurgeon who specializes in repairing spina bifida after birth.

Your baby will likely be delivered by C-section before labor contractions begin to lower the risk for damage to the spinal cord and surrounding nerve tissue. C-sections are typically scheduled at around 38 weeks of gestation (2 weeks before your due date).

Treating Spina Bifida

Before your baby is born, your fetal medicine specialist may discuss the option of open fetal surgery with you if both you and your unborn baby meet certain conditions. The surgery is performed between 24 and 27 weeks (6 months) of gestation and requires you to be put to sleep for several hours. During surgery, a large incision is made in your belly and on the uterus so that fetal surgeons can close the opening in your baby’s back while they are still in the womb. You are then hospitalized for 4 to 5 days and your baby is scheduled for delivery by C-section at around 37 weeks of gestation (3 weeks before your due date). This surgery is typically completed at around 34 weeks of gestation (6 weeks before your due date) and puts you at risk of premature delivery. There may also be additional long-term risks, such as difficulty with future pregnancies related to the incision on the uterus.

Evaluation After Birth

After birth, your baby's back will be wrapped in a sterile wet towel and they will be transported to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Your baby will likely undergo an ultrasound of the head after birth. A repeat MRI may also be needed, and your baby will likely be seen by both a pediatric neurologist and a pediatric neurosurgeon. Surgery may be performed within the first 24 hours after birth to repair the spina bifida. If there is evidence of severe hydrocephalus in the brain, you baby will be scheduled for a second surgery to create a new way for blocked cerebral spinal fluid to leave the ventricles. This can be performed in one of two ways:

- A ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt (thin tube) can be placed into one of the lateral ventricles and tunneled under the skin at the back of the neck until the end reaches and is inserted into the baby’s abdomen. A small valve opens when the pressure builds up in the ventricle and allows the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to flow down the tube into the abdomen where it is absorbed.

- An endoscopic third ventriculostomy (ETV) is a surgery where your pediatric neurosurgeon places a small endoscope through the baby’s fontanel to create a new passageway for fluid to leave the third ventricle of the brain.

Care Team Approach

The Comprehensive Fetal Care Center, a clinical partnership between Dell Children's Medical Center and UT Health Austin, takes a multidisciplinary approach to your child’s care. This means you and your child will benefit from the expertise of multiple specialists across a variety of disciplines. Your care team will include fetal medicine specialists, obstetricians, neonatologists, sonographers, palliative care providers, fetal center advanced practice providers, fetal center nurse coordinators, genetic counselors, and more, who work together to provide unparalleled care for patients every step of the way. We collaborate with our colleagues at The University of Texas at Austin and the Dell Medical School to utilize the latest research, diagnostic, and treatment techniques, allowing us to identify new therapies to improve treatment outcomes. We are committed to communicating and coordinating your care with your other healthcare providers to ensure that we are providing you with comprehensive, whole-person care.

Learn More About Your Care Team

Comprehensive Fetal Care Center

Dell Children's Specialty Pavilion

4910 Mueller Blvd. Austin, TX 78723

1-512-324-0040

Get Directions